GARY STEEL – “JUST ONE ASSHOLE. TOO MANY OPINIONS.”

Gary Steel has realised why his appreciation of music is different: he’s just not cultural. Please, let him explain.

REMEMBER ‘CULTURE’, THAT insanely catchy but utterly stupid song by the least “Dunedin sound” band that ever came out of Dunedin, The Knobz?

It was a song that was perfect for that moment in 1980 when someone really needed to give then-Prime Minister Rob Muldoon a swift kick in the nuts for having the unmitigated gall to declare that pop music was not culture (therefore justifying the baffling 40 percent tax on the sale of records).

There are many interpretations of the word “culture”, and most music scholars (musical anthropologists and historians) agree that music is part of culture, that its link to culture is inextricable and undeniable and therefore, very, very important.

Nevertheless, I don’t really care about all that.

In this month’s Metro magazine, Elsewhere editor/writer Graham Reid writes eloquently about Auckland Museum’s new exhibition of New Zealand music, Volume, leading his piece with a rumination about memories: how those of us with impressionist rather than photographic memories retain certain scenes linked to experiences of songs, and how important those snapshot memories are.

Reid discusses how an old song can raise other images, like a particular EP cover conjuring memories of “the family radiogram, the print of the raging sea above the fireplace.”

In the same issue, editor Susannah Walker and comedian Ruth Spencer both write about Boy George, and the wonderment of this boldly emblazoned gay icon bursting on the scene in the early 1980s with his band Culture Club. While I could relate to some extent with Reid’s radiogram analogy, the discussion around Boy George left me a little cold.

It’s true that Culture Club meant little to me, and that because I had already experienced the glam and new romantic movements, that I saw little new there. I mean, doesn’t anyone remember Jobriath? [It’s also true that I always found Culture Club’s music a little bit puffy and weak, but that’s another column.]

My dislocation at reading about Boy George (and about the Volume exhibition) was around the idea that this wasn’t really about the music at all, but around the culture of music, and a very public appreciation of the whole package. I found myself facing what could be my inner demon: that I’ve never felt part of a gang, or particularly in tune with the zeitgeist, and my appreciation of music has always pretty much been about the music itself, not the peripherals that many would claim as intrinsic to the culture of music.

So when I listen to blasts from the past, instead of thinking about the people I used to run with or who I was pashing at the time or throttling fat-necked dudes in the mosh-pit, my experience with music is much more personal, much more insular, much more… alone.

I guess that’s what happens when you grow up in a dull town like Hamilton in the ‘60s and ‘70s, are chronically shy, rather sickly, and never have many friends. I guess it’s what happens when because of all that, you never aspire to be part of a gang: music becomes a thing, apart from culture. It becomes the whole article, not the clothes it wears or the crowd that likes it or the drugs that go with it.

When you grow up like that, you’re aware of cultural movements, and the wave of popularity that some artists attract, but it’s of little import to your interior musical world, or how you appreciate what you listen to. There’s no internet, and few video clips, so you only know what you read about your favourite acts, in any case.

In addition to that I have to add that I never really identified with anything in particular, except for the rather poorly defined idea that the psychedelic rock movement represented some kind of revolution that was against parents, and the old-fashioned values they stood for, and was going to change the world. But that’s another column, too.

So like Reid and that radiogram and that room from long ago, my musical memories are mostly indoor memories that involve me, something to play a record on, and the record itself.

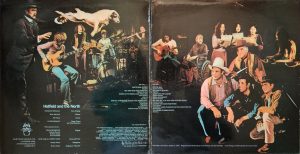

For instance, in 1974 on a family trip up to Auckland, I found an imported album by a group called Hatfield & The North in a K’Rd shop. They had been mentioned in the NME in conjunction with avant-proggers Henry Cow, so I spent all my pocket money on the album, with its shiny gatefold cover, grim picture of English suburbia, and inner jacket collage of American TV western characters, flying dogs, and the large ensemble responsible for the music within. The band were refugees from Canterbury (England) groups like Soft Machine, Caravan and Gong, and the album featured vocals by Robert Wyatt. I distinctly remember visiting my Aunty and Uncle’s house on the North Shore, where I was encouraged to put the record on their radiogram.

Usually, I listened to records alone in my room, and even my few close school friends seldom accompanied me on my listening expeditions, because frankly, I wasn’t interested in glam rock or boogie rock or country rock or Peter Frampton, and they weren’t interested in unpopular weirdness. So it was really embarrassing putting what turned out to be a particularly odd album (and one that quickly became one of my firm favourites) on my Uncle and Aunty’s radiogram, especially knowing that they were very traditional, very Christian, and that this was probably the first time that ROCK MUSIC had made it into their nice Jesus-loving house. It was all rather embarrassing hearing this extraordinary record (a mixture of difficult progressive rock, killer riffing, space-rock and jazz fusion with a Pythonesque sense of humour), and I played it at extremely low volume while everyone chattered over a nice cup of tea.

As mundane as it was, that memory has stayed with me.

Earlier, as a pre-pubescent lad, because I had become obsessed with music, and therefore records (and this included 78rpm as well as 45rpm, EPs and vinyl albums), it was only natural that I became infatuated with record players. At that stage we only had an old blue portable player of late 1950s vintage, and a good percentage of my parents’ collection were 78’s, so I thrashed those, even though I despised most of the music, which tended towards light opera and the more acceptable face of 1940s-style crooning: Bing Crosby, and war-time divas like Gracie Fields.

I just loved the whole mechanism, the needle in the groove, the feeling that a moment in time had been captured, and knowing that most of those old records were like ghost vibrations of people who were probably long dead. Then there was the smell – the musty burning dust smell that came from the record player itself, the smell of the records – and the tactile pleasure of touching those round things and their covers. Later, as an obsessive adolescent, I would import albums, tear off the shrink-wrap that NZ-made records never had, and inhale the smell within the orifice in which the record resided. But Gary-as-a-boy was hung up mostly on the sounds that record players made, and of course, there was the obligatory experimentation with intentionally wrong speed, and the awesome sound of just about anything made to go manually backwards.

I just loved the whole mechanism, the needle in the groove, the feeling that a moment in time had been captured, and knowing that most of those old records were like ghost vibrations of people who were probably long dead. Then there was the smell – the musty burning dust smell that came from the record player itself, the smell of the records – and the tactile pleasure of touching those round things and their covers. Later, as an obsessive adolescent, I would import albums, tear off the shrink-wrap that NZ-made records never had, and inhale the smell within the orifice in which the record resided. But Gary-as-a-boy was hung up mostly on the sounds that record players made, and of course, there was the obligatory experimentation with intentionally wrong speed, and the awesome sound of just about anything made to go manually backwards.

Music to me, then, was never about the live experience or about a song or a melody, but about recorded sound; a manipulation of music to enable the masses to hear a performance that often transcended the performance itself by utilising studio technology.

Back then, I didn’t know quite how they could get Bing Crosby’s soft crooning voice to sound so large against the musical backdrop, but it was entirely unnatural; crooning itself was the result of the advent of proper microphones and magnetic tape’s ability to capture the texture of the voice.

The music I was listening to in my 20s and 30s almost never inspires in me memories of fantastic concerts I went to or fantastic girlfriends I went with. My favourite records often have no memories attached to them except for me sitting alone in a room, listening to those records.

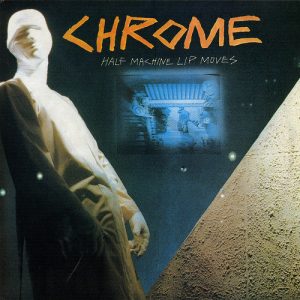

Very occasionally, there are memories of listening to music with a friend or two (for instance, I still remember perching on the edge of my bed in 1980 with my late friend Peter Corbishley, with Chrome’s garage-sci-fi at top volume, and I remember experiencing Brian Eno and David Byrne’s sampladelic My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts for the first time in 1981 with a small group of friends at Redmer Yska’s Oriental Parade flat, on both occasions off my little head on some hallucinogenic dak).

I guess what I’m saying is that, as interesting as I find the great arc of music as it relates to culture, it’s not necessarily the same thing that inspires me musically. I never felt that I had a culture, as a second-generation English immigrant to NZ, so a Peter Guralnick version of Americana (for instance), while anthropologically fascinating, was much less so musically.

Miles Davis is a perfect example. I can understand his place in jazz history, and acknowledge his cultural importance, but I own maybe two Miles Davis albums. On the other hand, I’ve got loads of albums by his former sidemen, like Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin, Tony Williams and Chick Corea. And there are many jazz artists who aren’t particularly famous or seen as culturally important who I love dearly, like for instance, Brazil’s Hermeto Pascoal.

Ditto David Bowie. That’s right, I’ve never really been a fan. Once again, I can acknowledge his cultural importance, and his particular genius, but only a part of that genius was musical, and a big part of it was choosing the right collaborators. On the other hand, I’m a huge admirer of guitarist Robert Fripp, and to a slightly lesser extent Brian Eno, whose contribution to songs like ‘Heroes’ made them great.

So here’s the thing. If there’s anyone else out there like me, don’t be humbled or shamed by the culture club. There’s nothing wrong with loving music for music’s sake, or loving the way that music comes together in a studio rather than as simply a representation of a real-time performance. And there’s nothing wrong with loving artists who are somehow out of time and generally unloved and not part of any great movement.

And if you are a paid-up member of the culture club, please don’t take offense at this little essay: I’m not saying you’re wrong. It’s obvious that music comes from culture, and sometimes represents a culture. I’m just saying that I look at things differently, and I refuse to be shamed for it. Sometimes, organised sound is enough. GARY STEEL

Brings back memories of Peter Corbishley selling his cast off 45’s to us in third form at St Bernards college.